Written by Niharika Rath

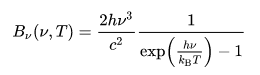

Plank’s law is used to calculate the energy per frequency of the light to get the number of photons per frequency.

This is divided by the energy of a single photon to get the energy per frequency.This spectrum is then multiplied by the response curve of the camera (Quantum efficiency) and the response curve of the filter (RGB data from Astronomik). These curves represent the photon detection efficiency of the camera and filters at different frequencies.

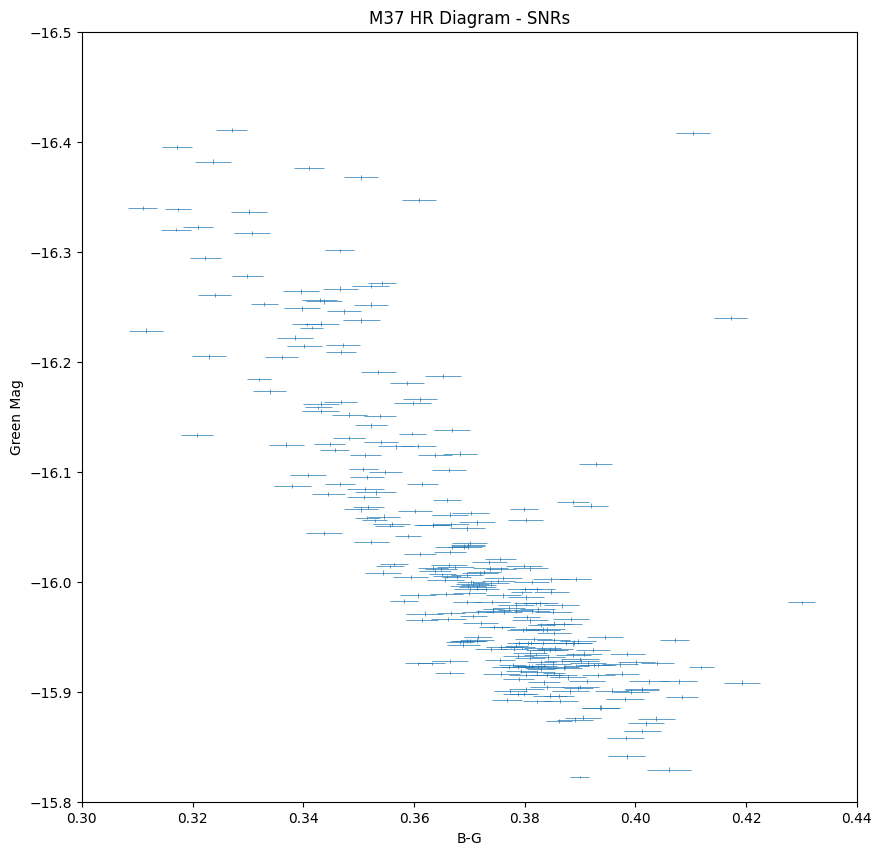

We integrate over the response curve spectrum at each frequency to determine the total number of photons that get through the filter to reach the camera.The results are tabulated in a three column table giving the temperature of the light source and the number of photons that get through the blue and green filters to reach the camera sensor. This allows us to estimate the expected flux of the photons reaching the camera sensor and comparing it with our flux values to gauge the spectrum response through the filters.

import numpy as np

from scipy.integrate import quad

import pandas as pd

# Planck's Law

def plancks_law(wavelength, temperature):

h = 6.62607015e-34 # Planck's constant

c = 3.0e8 # Speed of light

k = 1.380649e-23 # Boltzmann constant

wavelength_m = wavelength * 1e-9 # Convert wavelength from nm to meters

frequency = c / wavelength_m

energy = h * frequency

exponent = h * c / (wavelength_m * k * temperature)

intensity = (2 * h * c ** 2 / wavelength_m ** 5) / (np.exp(exponent) - 1)

return intensity, energy

# Load transmission data for blue and green filters

blue_filter_data = np.loadtxt('Astronomik_Blue.csv', delimiter=',')

green_filter_data = np.loadtxt('Astronomik_Green.csv', delimiter=',')

# Load quantum efficiency data for camera

quantum_efficiency_data = np.loadtxt('QuantumEfficiency.csv', delimiter=',')

# Interpolate transmission and quantum efficiency data

def interpolate_data(wavelengths, data):

return np.interp(wavelengths, data[:, 0], data[:, 1])

# Calculate total transmission through filters and camera response

def total_transmission(wavelengths):

blue_transmission = interpolate_data(wavelengths, blue_filter_data)

green_transmission = interpolate_data(wavelengths, green_filter_data)

quantum_efficiency = interpolate_data(wavelengths, quantum_efficiency_data)

return blue_transmission * quantum_efficiency, green_transmission * quantum_efficiency

# Function to compute the number of photons

def photons_per_frequency(wavelength, temperature, filter_type):

intensity, energy = plancks_law(wavelength, temperature)

total_trans_blue, total_trans_green = total_transmission(wavelength)

if filter_type == 'blue':

#filter_transmission = interpolate_data(wavelength, blue_filter_data)

ppf = intensity * total_trans_blue / energy

elif filter_type == 'green':

#filter_transmission = interpolate_data(wavelength, green_filter_data)

ppf = intensity * total_trans_green / energy

else:

raise ValueError("Invalid filter type. Use 'blue' or 'green'.")

return ppf

# Integrate the photons per frequency function

def integrate_photons(temperature, filter_type):

return quad(photons_per_frequency, 300, 1000, args=(temperature, filter_type))[0]

# Generate table of temperatures and number of photons

temperatures = np.linspace(300, 2898, 50)

blue_photons = [np.log10(integrate_photons(temp, 'blue')) for temp in temperatures]

green_photons = [np.log10(integrate_photons(temp, 'green')) for temp in temperatures]

# Create a pandas DataFrame

results_df = pd.DataFrame({'Temperature (K)': temperatures,

'Blue Photons': blue_photons,

'Green Photons': green_photons})

print(results_df)

results_df.to_excel('photons_results.xlsx', index=False) Temperature (K) Blue Photons Green Photons

0 300.000000 -2.318112 1.661602

1 353.020408 3.861581 7.237948

2 406.040816 8.436797 11.367775

3 459.061224 11.962380 14.551051

4 512.081633 14.763506 17.080613

5 565.102041 17.043649 19.139870

6 618.122449 18.936303 20.849181

7 671.142857 20.533090 22.291338

8 724.163265 21.898716 23.524593

9 777.183673 23.080279 24.591446

10 830.204082 24.110034 25.523573

11 883.224490 25.020600 26.344953

12 936.244898 25.829487 27.074464

13 989.265306 26.552946 27.726677

14 1042.285714 27.203924 28.313305

15 1095.306122 27.792870 28.843782

16 1148.326531 28.328306 29.325821

17 1201.346939 28.817258 29.765833

18 1254.367347 29.265564 30.169010

19 1307.387755 29.678124 30.539835

20 1360.408163 30.059073 30.882066

21 1413.428571 30.411932 31.198891

22 1466.448980 30.739715 31.493040

23 1519.469388 31.045017 31.766922

24 1572.489796 31.330085 32.022465

25 1625.510204 31.596877 32.261500

26 1678.530612 31.847103 32.485577

27 1731.551020 32.082266 32.696061

28 1784.571429 32.303693 32.894152

29 1837.591837 32.512557 33.080915

30 1890.612245 32.711132 33.257261

31 1943.632653 32.897873 33.424104

32 1996.653061 33.074859 33.582161

33 2049.673469 33.242839 33.732109

34 2102.693878 33.402484 33.874557

35 2155.714286 33.554401 34.010054

36 2208.734694 33.699141 34.139098

37 2261.755102 33.837201 34.262215

38 2314.775510 33.969034 34.379655

39 2367.795918 34.095054 34.491880

40 2420.816327 34.215637 34.599227

41 2473.836735 34.331203 34.702005

42 2526.857143 34.441918 34.800501

43 2579.877551 34.548149 34.894978

44 2632.897959 34.650164 34.985676

45 2685.918367 34.748209 35.072818

46 2738.938776 34.842511 35.156581

47 2791.959184 34.933282 35.237210

48 2844.979592 35.020716 35.314822

49 2898.000000 35.104928 35.389646